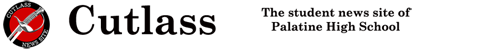

I gently lower the needle onto the spinning vinyl. A faint crackle breaks the silence. Suddenly, the air fills with the sound of a clarinet, its notes curling out in a smooth, woody warble, rising and falling like a gentle breeze. Without pause, the trombone joins in — its bold, brassy voice weaving around the clarinet in a playful, melodic dance.

As the band of French horns joins the congregation of sound, it becomes evident that each instrument is an individual playing for itself. Soon, however, a crash of drums ushers in a spectacle of sound. This melody is different, however; the instruments are no longer competing against each other. Instead, they work in sync, delivering a beautiful, unified harmony.

The drums beat with a steady pulse, anchoring the flurry of brass and woodwinds. The clarinet, trombone and French horns blend effortlessly, their voices merging into a rich, flowing sound. The music swells, building in intensity, as the instruments communicate in a way that words never could, each note an expression of pure emotion.

What I’m describing is my first time hearing George Gershwin’s 1924 jazz composition, “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Gershwin composed this famous piece of jazz history with a vision. “I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness,” he recalled to his biographer.

Gershwin’s vision of Rhapsody in Blue as a “musical kaleidoscope of America” captures more than just the sound of jazz — it defines the song’s role as a reflection of the nation’s many contradictions. Like America, jazz was born from diversity and conflict. It thrived in a nation that celebrated its artistry while marginalizing its creators.

One such example was The Cotton Club, a nightclub in Harlem that hosted some of the most well-known Black jazz artists of the era, including Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. Despite their undeniable talent and contributions to jazz, these artists performed for exclusively white audiences, as the club enforced strict segregation policies.

Black musicians were at the heart of jazz’s creation, yet they were often barred from fully participating in the very spaces their music helped define.

Despite the segregationist culture that plagued the United States, jazz culture helped transcend societal relationships beyond race. In 1935, Benny Goodman was among the earliest white musicians to include a Black musician in his band, defying societal norms and segregation laws. By the 1940s, more bands began to feature both Black and white musicians. Likewise, it wasn’t only the bands that were mingling; the audiences were as well.

Louis Armstrong recalled a Miami concert in 1948, saying “I walked on stage, and there I saw something I’d never seen. I saw thousands of people, colored and white, on the main floor. Not segregated in one row of whites and another row of Negroes … When you see things like that, you know you’re going forward.”

Jazz, like America, has always been a celebration of individual freedom, a space where musicians develop their unique voices and talents. But even as jazz constantly pushes for personal expression, it simultaneously weaves individual sounds into something greater. The tension between rugged individualism and collective unity is the essence of jazz and reflects many aspects of the human experience. As jazz historian Michael Verity explains, jazz “provided a culture in which the collective and the individual were inextricable, and in which one was judged by his ability alone, and not by race or any other irrelevant factors.”

In this way, jazz mirrors society’s melting pot — each person, with their own unique background and perspective, adds their own flavor to the mix to create something new and rich.

In reality, though, this doesn’t always happen.

Time and time again, we have become disconnected from one another —valuing our own beliefs over our shared humanity. Wars are fought over ideological and territorial disputes, tearing nations and families apart. Political polarization divides communities, turning neighbors into adversaries and relatives into strangers. We also fight over our cultural and religious differences. Instead of celebrating our differences as sources of rich diversity, we often resort to discrimination, violence and exclusion. Each of these struggles underscores our tendency to prioritize individual or group interests over the collective good, fracturing the bonds that tie us together as humans.

In my own life, I’ve felt this tension firsthand. When election season approaches, the atmosphere shifts, and everyone seems to take sides. Conversations that once felt effortless become battlegrounds, with friends turning into adversaries over political differences. I, too, found myself caught in the fray — it’s hard not to when the world around you feels so divided. In these moments, it’s as if the harmony that connects us as humans is lost, replaced by a discordant noise that drowns out understanding and unity.

Still, there are moments when our shared song resumes its harmony.

After the 9/11 attacks, it seemed like all was lost for many. Thousands of innocent lives were lost, and the feeling of security was shattered. This was a tragedy like no other. What happened afterward was unexpected. People across the United States and around the world united in unprecedented ways, finding solidarity in the face of tragedy. Political differences were temporarily set aside as people united. Our collective song began to play once more, as the crash of drums symbolized a unified response from all corners of society, regardless of culture or creed.

While the unity that emerged after 9/11 was a powerful moment of collective strength, it serves as a reminder that we can carry this spirit of cooperation and solidarity into our everyday lives, overcoming divisions and building a more united society.

Why is it that misfortune brings out the best in us?

I think that it’s because it strips away the superficial barriers that divide us. When a disaster strikes, it affects people indiscriminately. We no longer see others as strangers but as people experiencing the same fears and struggles.

Throughout human history, communities that worked together during challenging times were more likely to thrive. Social scientists call this cooperation “human altruism.” Despite thousands of variations between different cultures and religions. Altruistic behavior is a universal human behavior.

It can seem so easy to point out all these differences. But it is just as important to realize that there is more that unites us than divides us. Dance, food, art and music, bring us together in harmony. When we dance and sing, we celebrate life. We celebrate the millions of different, unique cultures.

I believe that our differences aren’t a bad thing — in fact, they’re our greatest strengths. Each person’s perspective, shaped by their experiences and background, contributes to a broader understanding of the world. In diversity, we foster innovation — where different ideas collide to create something entirely new.

The key to all this is cooperation. Just as in jazz, where every instrument adds its own voice to greater harmony, our differences can unite us into a powerful collective force. When we embrace and celebrate these distinctions, we unlock the full potential of what humanity can achieve together.

Jazz just flows. It’s unplanned, spontaneous, and in the moment. In that sense, we’re like jazz: each of us is a different person, playing our own melody, with our own goals, just trying to make our place in the world. And while we might not always harmonize perfectly, the ability to come together and create something meaningful is always within reach. Perhaps that’s why Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” still resonates with me nearly a century later — it reminds me that even in the midst of chaos, unity is possible, and the result is nothing short of extraordinary.