Stripped of innocence: how 9/11 shaped a school community

The morning of Sept. 11, 2001, began normally for millions of Americans. The sky was clear, the air crisp, and schools across the country opened their doors to an ordinary Tuesday. Then, at 8:46 a.m., the first plane struck the North Tower of the World Trade Center. By the end of the morning, both towers had fallen, the Pentagon had been hit, and another hijacked plane had crashed in Pennsylvania. Nearly 3,000 people were dead, and the world was no longer the same.

In classrooms at Palatine High School, teachers faced the unthinkable task of comforting their shaken students while trying to grasp the scale of the attacks themselves. Their memories carry both the shock of that morning and the weight of guiding young people through it.

24 years later, six of those teachers reflected on what they saw, what they felt, and how they remember that day.

It was Sean Fisher-Rohde’s second week teaching. He had just been hired as a science teacher at Palatine High School and was preparing to demonstrate Newton’s laws for his classes next period when the department chair, Debbie Craig, walked into the room.

“I was sitting in the back of the room at a lab station,” Fisher-Rohde recalled. “She came in through the front door and called over the teacher, Mr. Rogers Floyd.”

The bell rang as he broke the news.

“In a very calm demeanor, he said, ‘I just learned that a few moments ago an airplane had crashed into the World Trade Center in New York City.’”

Two questions hit Fisher-Rohde immediately: How could this happen? And why did it happen? As students began filing in asking about the attacks, he realized that Newton’s laws and the planned science demos didn’t matter.

“There were real emotions in my classroom,” Fisher-Rohde said, recalling a student who was “petrified” because she couldn’t reach her parents—her father was flying to Manhattan that morning.

With no working TV, no reliable computer, and no way to confirm details, Fisher-Rohde spent the day listening to students’ fears.

“The best that I could do was listen to fears, listen to concerns,” he said.

He tried to keep students from speculating while managing his own worry about family and friends in New York. He wanted to get a counselor, but he couldn’t leave the room. Teaching science that day was impossible.

Later, two physics teachers brought a small black-and-white TV into the science office, rigging it with an antenna so the staff could watch grainy images of the attacks replayed again and again.

“I remember calling my wife and talking with my friends here. What am I supposed to do? I can’t teach right now. I am too overcome with emotion, and the same with everybody else,” Fisher-Rohde said.

Eventually, he went to the media center and saw a larger color TV.

“I watched it for maybe 30 seconds. They were discussing the tower collapsing and people jumping to try and save their lives. I had a really hard time,” Fisher-Rohde said.

In the days after 9/11, he noticed how the nation, and the school, responded.

“You couldn’t pass a house in just about any neighborhood, including my own, without seeing an American flag,” Fisher-Rohde said.

Students and staff wore lapel pins; patriotic banners covered the football field.

“People learned what it meant to be a patriot, to stand behind a set of ideals and values that this country stood for,” he said.

The experience shaped how he viewed teaching.

“My job is about people, students first, number one. Everything else is secondary,” Fisher-Rohde said. Taking time to console students, help them call home, and listen to their fears left a lasting impression.

“Meeting the students’ needs has a profound impact on the kind of teacher I am today,” he said.

It was Erika Varela’s first year teaching culinary arts at Palatine High School. That morning, she was in her classroom with students, preparing for a lesson, when the news of the attacks began to reach the school.

“I was in class with my students, just studying some child development topic,” Varela recalled. “At first, all we knew was that a plane crashed. We thought it might be an accident, but then a second plane hit, and everyone realized it wasn’t an accident. It was an act of terror.”

As the day unfolded, the staff improvised ways to follow the news. “We didn’t have screens in the classrooms, so by the time we got to the media center, a couple of televisions were set up, and people were crowded around just watching,” she said.

Students were anxious and looking for answers. “People were asking if their families were safe, wondering if this could happen here. There were a lot of rumors, and everyone was trying to make sense of it,” Varela said. “I didn’t know what to tell them. I was scared too, and I had just started my first year. I felt completely unprepared.”

For the next week, Varela and her colleagues shifted the focus of their classes. Instead of teaching lessons, they guided students through activities that helped them process their emotions.

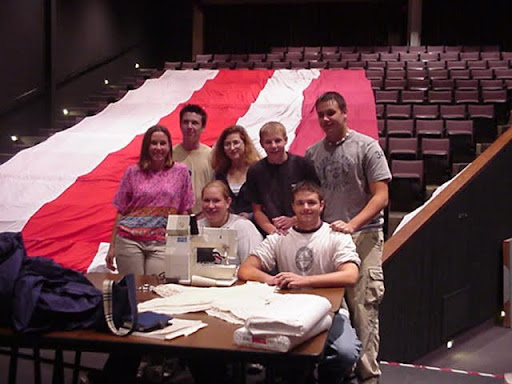

“In our classes, we basically stopped teaching for about a week,” she said. “We made red, white, and blue bracelets. We helped cut out stars and sew together a huge flag. There were sewing machines set up in the gym, and students worked together on this permanent display. It really unified us.”

The tragedy changed routines at the school. “After 9/11, we started saying the Pledge of Allegiance every day,” Varela said. “Students were more patient and understanding with each other. We realized what was really important—talking to the kids, helping them process, and just being there for them.”

Varela reflected on how the experience shaped her as a teacher. “It taught me that teaching isn’t just about lessons or recipes. It’s about people, helping them feel safe, and guiding them through moments they can’t control,” she said. “That first week after 9/11 showed me the importance of empathy and community in the classroom.”

Joyce Richardson, a teacher and mother, wasn’t scheduled to start teaching until fourth period on Sept. 11, 2001. That morning, she had been caring for her son and attending a boys volleyball meeting.

“Suddenly, I came into the office, and someone said, ‘Hey, there’s something that happened in New York. A plane crashed into one of the Twin Towers,” she recalled. At first, she thought it was a terrible accident. By the time she returned from errands with her son, news of a second plane had emerged.

“I was like, wait a minute, why two?” she said. Later, at home, she watched the first tower collapse. “The first thing I did was text my college roommate, who’s originally from New York, and I was worried about her family. She said they were safe, watching from London,” Richardson said.

Reports of the Pentagon and a possible fourth hijacking added to the fear. “It was like a free fall. Everybody was scared. Are we under attack? What’s going on?”

At Palatine High School, the atmosphere was surreal. “We didn’t have the kind of instant news on our phones that exists today. All we could do was watch TV updates—story after story of people trying to contact loved ones—and there were no regular programs, just nonstop coverage.”

In the weeks afterward, the community came together. Richardson recalled a school-wide project led by teacher Fran LeBeau. “We wove together a giant American flag quilt as a community. The students needed something to grasp onto. They asked, ‘What can we do? How can we help? How should we show support?’”

Richardson said the attacks left a lasting mark on students and staff. “It broke my heart to see the students stripped of that innocence. They realized that someone could purposely do this to hurt others. It was a moment that changed how we viewed our roles as teachers and as a community.”

Leslie Schock had just graduated from Northwestern University the previous December. After taking extra time to complete student teaching while playing basketball, she stayed in Chicago with a college friend, working odd jobs and enjoying city life.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, Schock woke up and turned on the TV. “I saw the first Trade Center building on fire. At that point, everyone thought it was a freak accident. How could a plane accidentally run into a skyscraper?” she said.

Then, live on television, a second plane struck the other tower. “It was like this catastrophic event captured live and experienced live by Americans all across the country,” Schock said.

Schock was scheduled to start a shift at a sports bar north of the Loop, but the mayor ordered an evacuation of downtown Chicago, fearing the Sears Tower could be a target. With mass transit shut down, thousands of people streamed out on foot. Many stopped at Schock’s bar, drawn by the TVs showing the attacks. “We all watched the first tower fall, and then the second. It was surreal—people screaming, crying, grown men sobbing. A complete lack of belief that this could happen,” she said.

The devastation was staggering. “Eighty thousand people worked in those buildings. We didn’t know who had gotten out, who was still inside. And we knew first responders were in there,” Schock recalled. “Even the newscasters were struggling to hold it together. It was the moment of my generation. My parents have JFK; this was ours.”

People speculated about who was responsible, and news reports suggested a terrorist attack. Schock remembered the difficulty of communicating with friends in New York. “There were no smartphones. Cell towers were down. Planes were grounded. We were hit with unbelievable news, one story after another,” she said.

While most coverage focused on New York, reports from the Pentagon added to the fear. “Everyone was terrified and worried Chicago could be next,” Schock said.

Katie Kupka was starting her third year teaching at Palatine High School when the attacks happened. She taught her first-period class and heard the news as she walked back to the English department.

The school’s technology was limited; TVs were still being wheeled in to show movies, but in the teacher cafeteria, “they had a TV in there, and so everyone was down there watching all the coverage.”

At first, she didn’t even know how to process it.

“You didn’t really know how to react. It was like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” Kupka said.

The days that followed left little room for traditional instruction. “The message was to be there for our students and support them in any way. Feel free to talk about it,” Kupka said.

She remembered a sophomore telling her, “‘My parents want me not to worry. They say focus on school.’ She was upset because it really affected her. It was a real loss of innocence for kids of that time.” Teens realized that history wasn’t just something in books, it could arrive in an instant.

Outside the classroom, the shock carried over into everyday life. As an assistant coach for the girls’ swim team, Kupka watched all activities get canceled. She drove home to her parents’ house in Schiller Park and finally let the tension of the day go.

“I kept it together all day, like I was fine… but as soon as I saw my parents, I just lost it,” she said.

Her boyfriend, working downtown in the Prudential Building, had been evacuated and navigated public transit to get home.

“When I finally talked to him, he was crying. It was one of those first moments where everyone was in despair. It was like a combination of grief and fear—all one,” she said.

Kupka said she also noticed a rare sense of unity.

“Americans were so united. I never experienced that kind of fierce unity and honor being an American. It was beautiful to experience, even though it was short-lived,” she said.

At school, that unity became tangible. Led by Family and Consumer Science teacher Fran LeBeau, students and staff made a giant flag quilt from donated red, white, and blue sheets. It was displayed at school events, professional sports games, and eventually at a site in Pennsylvania.

“No teaching was happening. Everyone was coming together to make sure kids were okay. For a brief moment, there was unity,” Kupka said.

Colten Hilgers • Sep 11, 2025 at 2:29 pm

Never forget 🇺🇸